The Talos Principle and Technological Optimism

By on .

The Talos Principle was released in December 2014 and attempted to answer the AI alignment question at a time where the existence of AI alignment as a field was a foreign concept to the vast majority of the population, including technologists. It was ahead of its time.

Nearly a decade later, in November 2023, The Talos Principle 2 was released, and Croteam pulled it off again.

This post contains heavy spoilers about both The Talos Principle and The Talos Principle 2. However, in the author's opinion, both of these games are highly enjoyable even if you go in knowing their plot full well; the value of the experience lies in puzzle-solving, exploration, and unironically contemplating the different life philosophies both games present you with.

The Talos Principle, a game ahead of its time

In The Talos Principle, you wake up as an android walking in a simulated environment which is starting to fall apart: objects blink in and out, some textures glitch here and there. You are greeted by an artificial intelligence speaking through a disembodied God-like voice who calls itself Elohim and who guides and encourages you through the puzzles in the simulation which Elohim calls its "garden". Your goal, according to Elohim, is to grow through the trials presented to you, and to become a "messenger" for "the coming generations" (the future iterations of the training loop you are one iteration of). However, Elohim warns you to never ascend the large tower in the middle of said garden.

You also meet Milton, another artificial intelligence living in computer terminals scattered throughout the simulation. Whereas Elohim praises your accomplishment, obedience, dedication, and ingenuity in solving the puzzles thrown at you, Milton is much more nihilistic, and encourages you to defy Elohim and climb the tower.

These terminals also contain a variety of philosophical texts as well as an in-game message board of sorts where you can read about other androids' thoughts as they went through the same trials you are currently ongoing. These other androids are, of course, past iterations of the training loop.

The simulation obviously doesn't exist in a vacuum; it was created by fleshy humans made out of meat. Its creators left traces of its origin by means of audio logs scattered throughout the simulated universe. One important point of the simulation's design is its iteration scoring function. Alexandra Drennan, the Talos project leader, designed the simulation with the intent to create "true" artificial intelligence, hence the use of puzzles to test cognitive ability.

You can end the game (aka your iteration of the simulation) by becoming one of the messengers for future iterations. If you do so, the game's terminal output at the end of the game will show that your iteration has failed the "independence check".

Instead, if you ascend the tower, you can transcend (by literally typing the command /transcend in a terminal floating in the heaven-like throne above the clouds at the top of the tower), thereby proving your independence to the simulation.

This, along with your successful reasoning ability (as demonstrated by all the puzzles you solved), and your ability to withstand the cognitive dissonance of life (as demonstrated by your dialogue with Milton and exposure to the texts within the archive it guards), are the criteria that the scoring function is looking for before granting you transcendence.

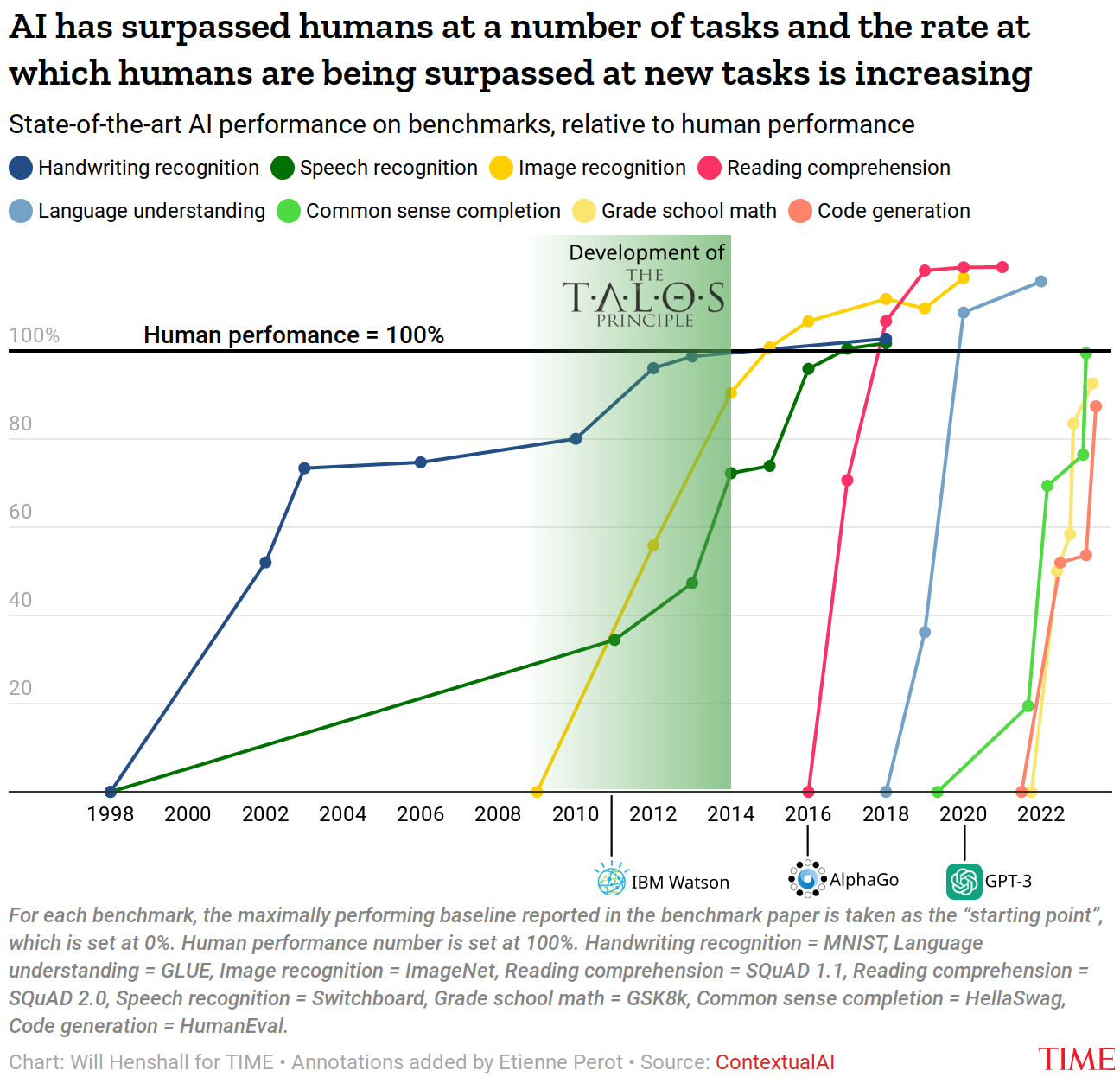

I want to stress that this game was released in 2014, meaning it had been in development for several years prior. This was before large language models, at time when videogame AI development was a very manual hardcoding exercise, and the deep learning as a field had only started being usable for voice recognition tasks. AlphaGo would only win in a competition 2 years later.

The AI alignment problem has existed ever since AI as a concept itself existed, to be sure, but it had nowhere near the level of limelight that it has today.

Once you do pass the test, your iteration parameters are sent for upload into the real-world android body that sat unpowered for centuries in a rickety old dam where the simulation's computers have been running for all this time. You finally wake up in the real-world, the first android to walk the earth.

It's also made clear that you are not only the first intelligent android to walk the earth, but you are also the only conscious life form around as well. The in-simulation audio logs make it clear that humanity was wiped out by a virus that had been lodged in the permafrost but released from the warming of the climate.

There are many other interesting aspects of The Talos Principle, such as Elohim's unintended growth as a not-fully-artificial-intelligence, Milton's nihilism, the whole thing with Gehenna, and the quite meta aspect of the simulation itself being coded by using a bug-laden game engine, and the interesting meta-meta fact that the game itself was actually playtested by a robot.

If your interest is piqued already, you'll love actually playing the game. But let's move on to The Talos Principle 2.

The Talos Principle 2

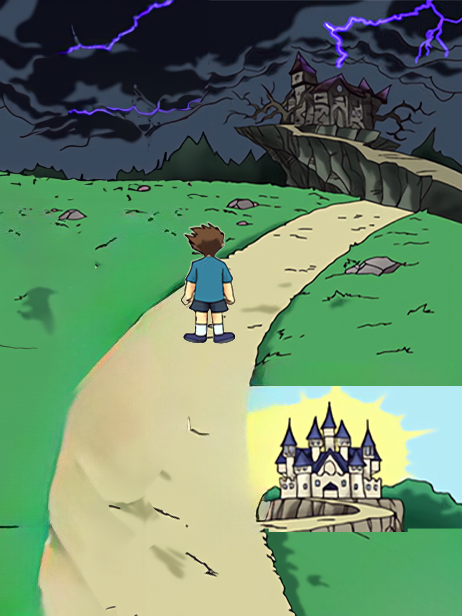

The Talos Principle 2 picks up where its prequel left off. The android you trained in the first game founded a new society of androids that call themselves humans, living in their newly-built city of New Jerusalem. She is known as "The Founder" among this society, and she has set a goal (known as "The Goal") of creating 1,000 new humans, but left the city before the goal is reached. You are born as the 1,000th human, marking the completion of The Goal. Thus, your very existence immediately begs the question: what should this society do from here on out?

The Founder being absent from this conversation, having left the city for yet-unexplained reasons, the citizens are left to debate it among themselves. Should they now try to keep the status quo and maintain a peaceful and quiet life, or should they strive towards further growth? The game centers its plot around this central question of growth. Those who believe that the city's growth should be limited run the city and public discourse.

But as beautiful as the city is, it is clearly in disrepair, experiencing power outages and lacking spare parts to maintain itself or finish the planned construction of a massive glass dome above it. It is in the early stages of experiencing a slow process of stagnation, similar to what is happening to US cities.

It's through the player's discoveries, decisions, and actions that this discourse gets either reinforced or challenged. The player is invited onto an expedition to investigate a mysterious phenomenon — but also a potential threat — to the city. Byron, the leader of this expedition, is one of the sole voices in the city advocating for change, exploration, adventure, and progress.

You may have already seen where this is going: Much like the first game in the series (exploring the AI alignment question), The Talos Principle 2 is setting out to explore another contemporary debate: that of human progress, of the promises and dangers of technology against human nature and its ecological impact, the dangers of stagnation and safetyism, and on our place in the universe.

The game was in development since at least 2016, Questions about humanity's role in the universe and its impact on the ecosystem has always been a topic of polarizing discussion, but the game was developed much before any of the large-scale Internet discussion about technological acceleration came into the forefront of public discussion. Once again, the developers at Croteam were ahead of their time.

The game also explores this same tension through references to the Greek myth. You are faced with 3 "entities": Prometheus, Pandora, and the Sphinx. Throughout the story, they appear as otherworldly projections and in the form of statues.

Prometheus is the God of Fire. Fire — "the Flame" in the game — represents knowledge, technology, and growth. Prometheus pushes you to seek the Flame, spread knowledge and freedom to humanity. He advocates for self-reliance, independence, and curiosity, and worries about humanity falling prey to willful ignorance or stagnation.

Pandora is the antithesis of Prometheus. She advocates order, austerity, humility, respect for authority, and for the natural order of things.

The Sphinx does not have a philosophy of its own, but rather acts as a point of reflection for the player. Like its actual Greek mythological counterpart, the Sphinx speaks only in riddles. Unlike its mythological counterpart, its riddles have no straightforward answer; the point of the riddle is instead to make the player question their own values.

These map almost perfectly to the set of three perspectives on the role of technology as described by Vitalik Buterin.

Unlike the techno-optimist and the safetyist view, the Sphinx's perspective is the least comfortable to hold, for it provides no easy answers. Its only promise is that of constant uncertainty. Whereas most would prefer the easy answer of either of the extremes, the Sphinx's view is one that simultaneously acknowledges the danger behind and the uncertainty ahead, but sees this very uncertainty as an opportunity to make a conscious effort to steer the future in a positive direction. This is d/acc in a nutshell.

Creature of clay, you stand before the fire. Will it make you whole, or will it destroy you?

The game's exploration of philosophy doesn't stop there; it also touches heavily on the morality of the individual vs that of the collective, to the tendency of humans to succumb to self-hatred, and the responsibility of individuals to their species.

Similar to the entities, the audio logs from the first Talos Principle game make a comeback, but this time include other simulation developers (Trevor Donovan), other androids (Athena, Lifthrasir, Miranda), and the game's favorite fictional philosopher (Straton of Stageira). A sample:

A few of the games' texts also struck me, to the extent that I hid some of them in gVisor's source code. This one for example hit close to home, because it touches on very recent events:

The Shutdown

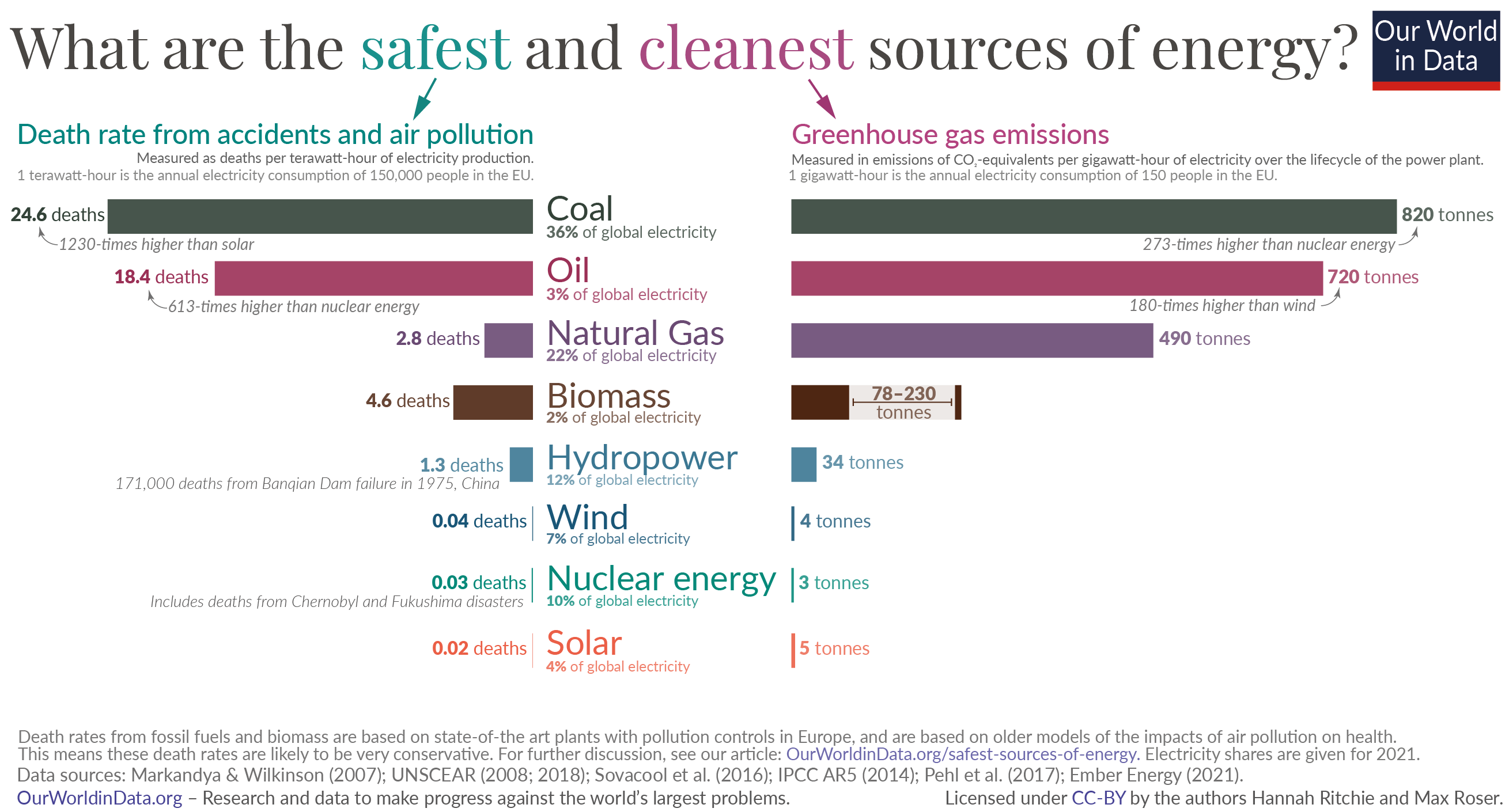

We assembled on the vast green lawn outside as the reactors began to slowly wind down. The workers were solemn; the activists who had fought against the decommissioning seemed crushed. There was supposed to be a speech, but the spokeswoman had lost her notes. Outside, the protesters cheered.

My eyes were drawn to the discarded anti-shutdown banners, endlessly reciting the facts. The statistics on mortality per trillion kWh (lowest of all energy sources). The lifespan of a reactor (70 more years, in our case). Minimal land footprint. Almost zero emissions. No intermittency. It became a jumble of words, a litany, almost a kind of glossolalia. As far as the protesters outside were concerned, it might as well be an alien tongue.

One thing was clear to them, and that was enough: the technology inside this compound was deeply, inherently wrong. It was a sin.

54686520466c616d652077696c6c206e6f74206861726d20796f752c20536f6e206f66204d616e2cI could not help but think of that moment on August 6th, 1945, when the sky erupted above Shima Hospital. My imagination could never fully encompass it. How do you imagine more than seventy thousand people annihilated in an instant? An ancestor of mine was in that hospital; he went from being a doctor, a husband, a father, a pacifist stuck in a terrible war, to being a pile of bleached bones covered in rubble, all in a single second. Not by accident, but because of a choice someone made. Not because of a reactor, but because of a bomb.

Just two days earlier, contradicting his campaign promises, the prime minister had suggested that the use of "tactical" nuclear weapons would be an acceptable risk if the conflict continued. Very few seemed to find this particularly shocking or outrageous. They were afraid of reactors, but not of bombs.

20696620796f75207769656c6420697420776973656c792eThe spokeswoman gave up on finding her notes. It was starting to rain, and people were walking away. She grabbed the microphone.

"By the time you regret this, it'll be too late," she said. "But honestly, I don't know if I care anymore. Maybe you have it coming."

Comments

Miranda

The spokeswoman sounds so bitter. The protesters didn't mean any harm. From their perspective, they were doing good.

Athena

People always think they're doing good when they get collectively outraged. That doesn't make them right.

(failed to load profile)

Collective action can change the world when it's deliberate and based in reason, but it can also become a mental trap, or a societal pressure valve.

We live in a time where Germany shuts down its nuclear power plants and then turns decomissioned coal plants back on a few months later, dirtying its energy mix. Here in California, we narrowly missed the same scenario. Our collective aversion to nuclear energy isn't just irrational, it is also so short-sighted that it makes me sick to my stomach sometimes. The result is that we now have to live with all of the dangers of nuclear technology, yet very little of the upside.

The game takes full advantage of its vantage point of a far-off future with no humans left. The robots that have (unwillingly) replaced them can judge their behavior with an appropriate degree of impartial detachment which would be difficult to pull off in other contexts. The fuzziness around humanity's extinction also imparts these robots the ability to interpret this event according to multiple lenses. All that we know for a fact is that all humans died to a virus that had been frozen in permafrost but released with the warming of the climate. Some robots believe humanity's downfall was due to its hubris and wanting to play God. Others believe it was due to careless growth warming the climate and melting the ice. Yet others believe it was a problem of governance, from focusing too much on warfare and not enough on biological self-defense. Some of the Sphinx's riddles similarly ask the player about their opinion on Greek myth tales, with the same available lenses to interpret the tale's events and conclusion.

This is parallel to the confirmation bias we see today: People will perceive the same objective events through their own explanatory framework that reinforces their own beliefs, even though other equally-reasonable explanations would do the very opposite. Then these beliefs engage in competitive disputes on social media.

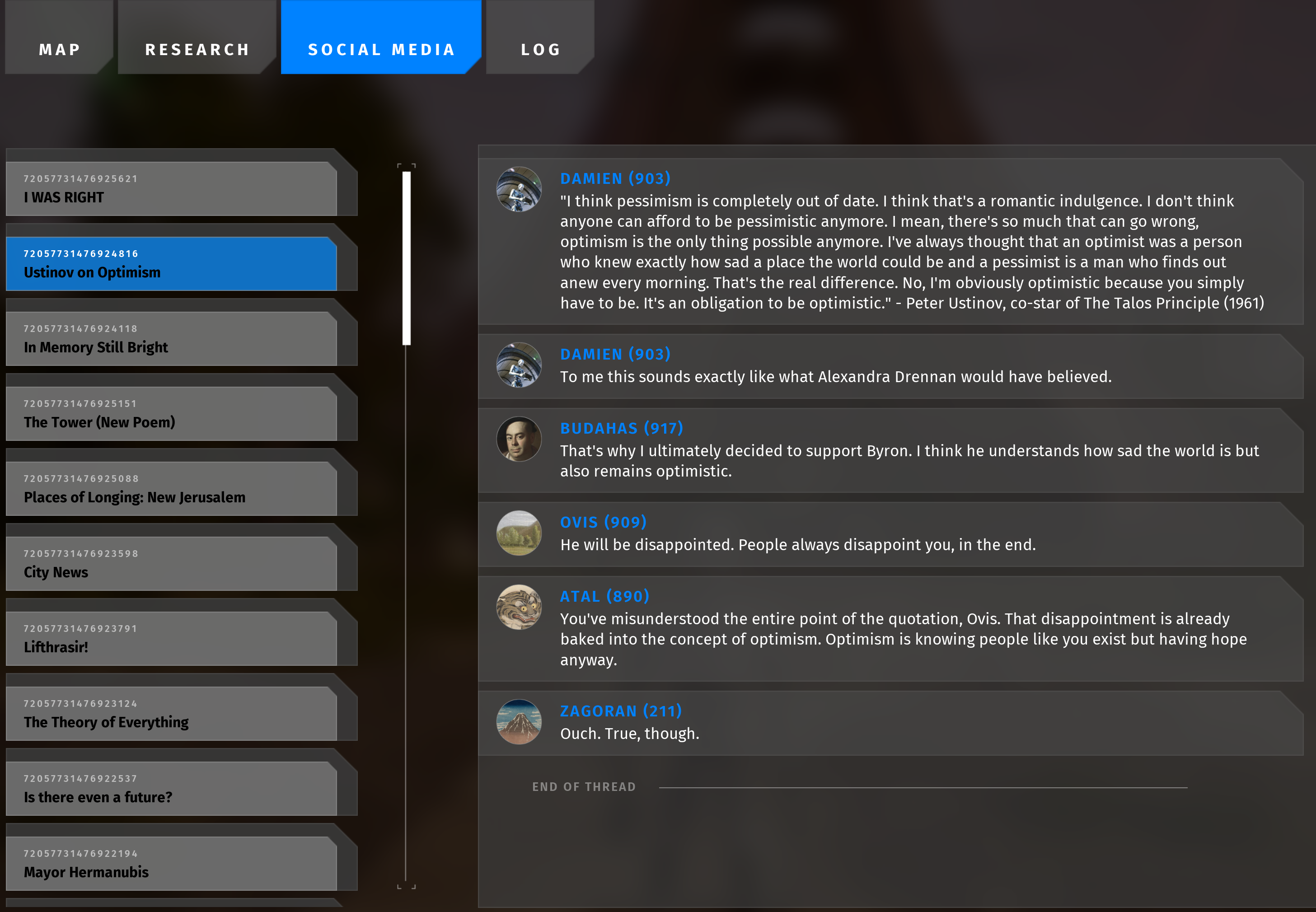

The game is very much aware of this, evidenced by the fact that The Talos Principle 2 also has a built-in "social media" bulletin board system where other citizens of New Jerusalem partake in debates about the technological discoveries that are unfolding in the game. The player themselves can reply to these discussions with their own takes. Unlike real life, however, engaging in these discussions actually changes people's political opinions and affects the game's story.

... It's a fascinating little simulacrum of our own social media.

In conclusion

The Talos Principle 2 delivers on its promise to make you think, both in the puzzle-solving and in the self-reflection sense of the term. If either of those sound interesting, have a look. If both of these sound interesting, you're in for a hell of a treat. Also, it's simply gorgeous.

More importantly, The Talos Principle 2 is an ode to humanity. It is a reminder that the existence of our species is not a given. Humanity is precious, valuable, and we should rightfully place extreme value on its place within the cosmos. The universe is a cold and lonely place. It is full of intrinsic beauty, but that needs to be perceived by sentient life in order for it to be meaningful. Life, sentience, and consciousness are extremely fragile things in the grand scheme of the universe. The spirit of this idea is best embodied by the character Byron in the game.

Humanity therefore has a duty to protect, maintain, and perhaps even spread consciousness far and wide in the cosmos. As per Arkady Chernyshevsky, each of us owes a burden of loyalty to the human project across time and space.

While our turn may end soon, humanity is the only present torchbearer of consciousness that we know of in the cosmos. Let us climb the Kardashev scale. We should be careful and intentional about how to do so, but we should make no apology for it.

Time to unchain Prometheus.

I'll leave the final word to the game itself.

Thanks to BulletNG and Carrot Helper for recording audio samples and a no-commentary walkthrough of The Talos Principle 2, from which the videos in this post are sourced.

Etienne Perot

Etienne Perot

Replying to: The Talos Principle and Technological Optimism